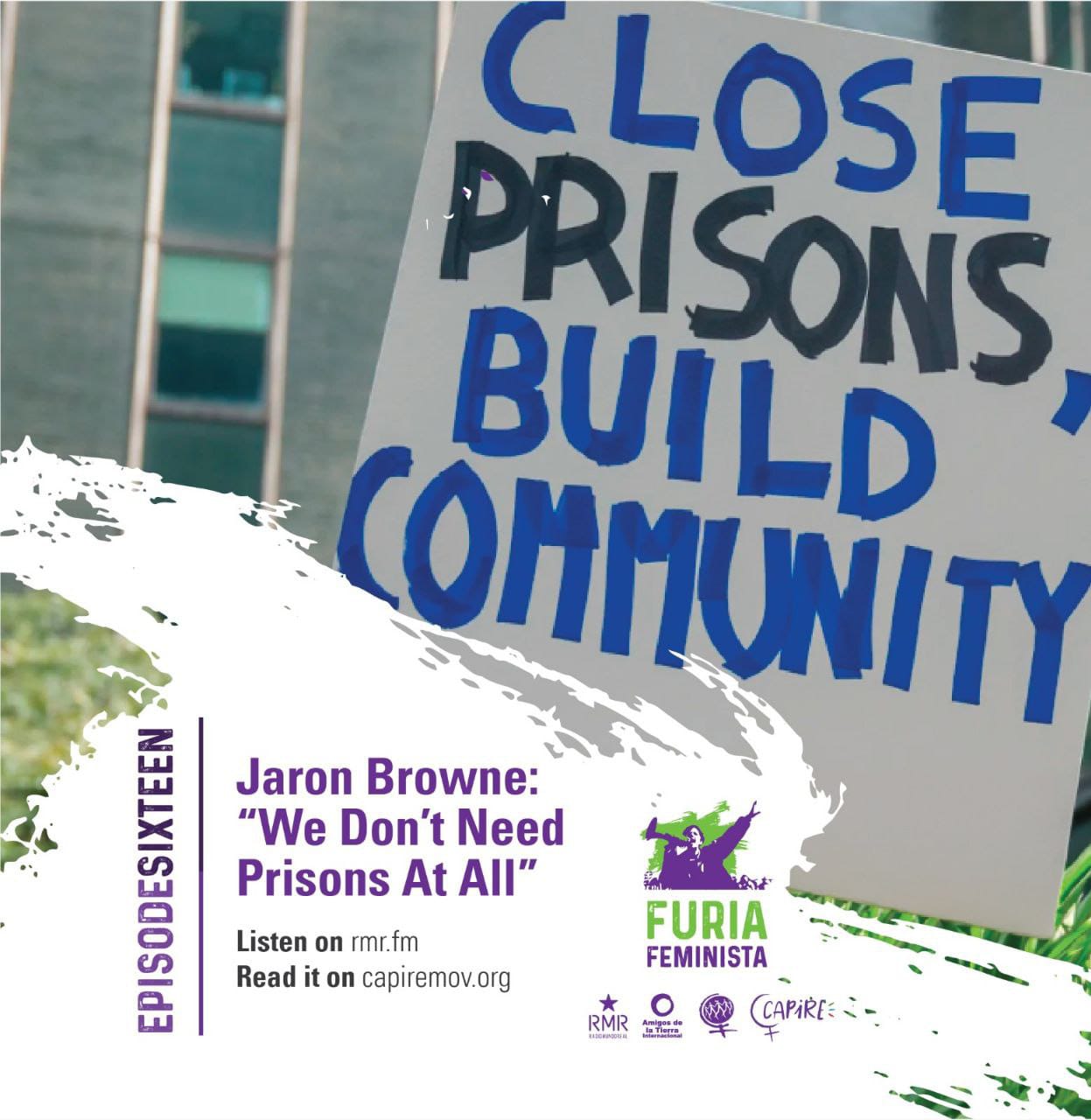

Jaron Browne: “We Don’t Need Prisons At All”

Interview conducted on the show Fúria Feminista on prison abolition

Jaron Browne is the director of the Grassroots Global Justice Alliance (GGJ) in the United States. He attended the meeting “Weaving Emancipatory Proposals” in May 2024 in Guatemala, where he granted an interview discussing prison abolition, a struggle emerging from anti-racist organizations. Jaron, a trans person, underscored how important feminism and organized LGBT+ people are for the abolition struggle.

While the interview is mostly based on experiences and accumulated knowledge from the anti-prison struggle in the United States, prisons are an issue across the Americas and the world, used as a way to control and maintain capitalist, racist, and patriarchal violence. In El Salvador, for example, the right-wing government of Nayib Bukele has imposed a regime of exception and built the largest prison in the Americas, with capacity for nearly 50,000 people. In two years between 2022 and 2024, 78,000 people were imprisoned; human rights organizations have reported that 244 people have died under state custody and there are thousands of cases of human rights violations.

The recording of this interview was originally released on Real World Radio as part of episode 16 of the show Fúria Feminista, produced by RWR and the World March of Women Brazil.

What is prison abolition?

To us, the relevance of the concept of abolition is in allowing us to understand that the prison and punishment system is deeply rooted in the history of slavery. There were no prisons in North America before slavery. What the feminist abolition movement proposes is to show that this form of castration is not necessary at all. It is rather extremely harmful to communities, specifically African-descendent and Indigenous communities. It is a violent system, a racist system. So abolition is an alternative to promote safety and justice for everyone.

Prison is not a solution for issues of safety and violence, because it actually sustains and maintains violence. What are the abolition movement’s strategies to stop incarceration? What is the defunding proposal?

We are talking about defunding and shutting down prisons. Defund the police, including the immigration police, and other violent forms of controlling people. Instead, there are many other ways to introduce safety and justice and face conflicts. We should mention that, in North America, this perspective is coming from African-American feminist movements. In the United States, right now, we have the largest number of people incarcerated in the world.

There are more than 2 million people incarcerated in the United States. Most of them are people who have never committed a violent act. Most of them are victims of a capitalist system and of poverty. Most people who are incarcerated are there for social reasons, and also due to a system of discrimination.

This was the only thing that has existed for a while for people in crisis—a violent act that causes a horrible impact for generations. This is why the idea of pushing alternatives emerged, with a vision that we really do not need prisons at all. Period.

Defunding is very important. If we look at the huge cost of each incarcerated person—a woman, a mother, a man, a transgender person—, we can see that it is thousands of dollars a year. It is much more if we imagine these 2 million people imprisoned in the United States. What can be done with these funds? We could improve these people’s access to health care, rehabilitation, education, sustainable housing, things like that. To me, this is the beginning of this struggle: with all the money they are using to build prisons, what happens if we invest it in the community, in education, and good community services? It’s possible, and this is the demand that has emerged in the past two decades and continues today, in the United States and in the world.

Women and sexual diversities suffer specific impacts and consequences in prison, including sexual violence perpetrated by guards and the police. Can you talk about your views on this matter?

There is a global crisis of violence against women. But if we can look at the root causes of this violence, how can we ensure real safety? This is part of what we need. It’s not that we want those who are raping them to go to a place where they will endure more violence. Also, with our police system, women often call the police in moments of crisis, but then the police come with their aggressive approach, which may not be safe for women either.

This is why we are establishing other organizations, with new things to come. How can we organize to provide a community-based response? How can we invest, before a crisis occurs, in resources to create safe communities? The safest community is not one where there is more police presence or more prisons—it’s the community that really has more resources, with schools, places that provide health care and healing, food. These are the things that ensure a community, and you can feel that. But when we live under economies with so much inequality, we feel that we need the police, we need prisons. It’s a situation where there is a lot of violence and suffering, and this is changing. We are changing.

How are these changes happening? How can we change the impacts of prison confinement on families and communities?

The organizations are very powerful. I want to mention Courage, which is a member of GGJ and an organization of young people impacted by incarceration. Their motto is to shut down youth detention centers and educate young leaders. This is their practice, with political education. These young people come from the community with great leadership. What I can observe in these situations is that, when someone is imprisoned, the whole family is affected. They try to maintain connections, visit their families, look for opportunities to spend birthdays together, but it is really hard. It’s hard to only get visits and calls. It’s damaging to entire generations. Many young people talk about the incarceration experience of their parents or family members. This is especially hard on women, and maybe it is part of the reason why the abolition movement comes from Black feminism, from Angela Davis’ thought. There are many African-American women with this perspective on abolition.

I also want to mention the very serious situation endured by transgender people, because prisons are very dangerous for them. There is a very important struggle and specific organizations for transgender people who are incarcerated. One of them is the Transgender Gender-Variant & Intersex Justice Project (TGIJP). An important leader of this organization was Miss Major. Her view and compassion were so powerful. After her, many more women are talking about how they are criminalized, specifically as transgender women. When they are imprisoned, they are often victims of rape and violence. This is why they are strong in their action and activism and provide a very important contribution to the abolition movement in general.

What kind of alternative justice is there to the current punitive justice system?

The restorative justice idea is mainly centered around accountability. These are processes centered around the experiences of the people who are impacted, while allowing us to be aware of everyone’s humanity. The person responsible for hurting someone else has likely experienced violence in their life too, and maybe they have also been a victim. The process of restorative justice includes many ways of working on this based on the wishes of the affected person. There are many organizations that practice that and the people who take part in these processes often experience an amazing transformation. None of us is reduced to the ugliest act we have committed in our lives. It’s important to face these acts and be accountable for them. I have heard from people who have been victims that, when they have the opportunity to participate in a process like this with someone, it is much more comprehensive than the experience of having someone incarcerated. It’s complex, but it’s a very important process. We can learn a lot from the experiences that are already happening in many different places. It’s happening in schools, in communities. It’s an advanced process in its practices, and it has a lot of potential.

To understand the concept of restorative justice, it’s important to define what safety is. How can we advance in this sense?

The beauty of this idea comes from Angela Davis, a very important African-American feminist from the United States. In the movement for justice, we can also look at incarcerated leaders, like George Jackson. Now I think the idea is connected to many organizations, like the Black Lives Matter movement, among other African-American movements in the United States, including Dream Defenders and BYP100. Abolition is a very powerful idea now, and it has also been a powerful idea to Chicanos, political prisoners in Borinquen, Puerto Rico. After Black Lives Matter, we have been able to promote these abolition ideas at the global level. We talk about defunding the police, in a great moment of people’s awareness, saying that we really do not want the police that are killing African-American children.

We are coming to the end of our conversation. Would you like to say anything else about alternatives to prison punitivism?

In many ways, especially in the North, we are spending billions—even trillions—of dollars in violence, war, bombs, police, and prisons. We have a capitalist economy that is an economy of death, an economy of violence. We can see the impact of this violence across generations. The awareness that is coming now from the grassroots feminist movement shows that we can promote an economy of life, an economy of care that values everyone.

With this, we are advancing toward a view on safety that puts much more effort in healing, rehabilitation, community resources, and opportunities. When you have these views, including restorative justice, when we invest in these options, we can look at completely different possibilities. There are examples of this around the world. To name one, Iceland has one of the biggest examples, in a very serious situation. Someone walked in with guns and killed a lot of people. This happens a lot in the United States, in what we call mass shootings. In Iceland, when that happened, the progressive government decided to invest in more opportunities, work, and youth centers for people from their childhood. This completely changed the situation of violence in the country. I hope we can have more exchanges, because there are movements addressing this in other parts of the Americas. In our feminist movements, the idea of potential leaders from all impacted communities is fundamental.

—

By Capire and Real World Radio

Interview conducted by Valentina Machado (Real World Radio)

Intro by / Edited by Helena Zelic

Translated from Portuguese by Aline Scátola

Original language: Spanish